When Tibetan Women ruled Tibet

In my attempt to engage more historic female figures in Tibetan history, I’ve decided to share a close reading of Janet Gyatso’s “Down with the Demoness: Reflections on a Feminine Ground in Tibet” (1987). Through an engagement with historic female figures in gendered histories of Tibet, I hope to find out more about Tibetan women and societies of our shared pasts and how we want to go about understanding our histories and ourselves in the present. This is also a continuation of a conversation I began with “On Being Tibetan and a(n) Intersectional Feminist,” to look deeper at Tibetan histories with gendered lens. I hope this close reading brings you the same excitement it brought me.

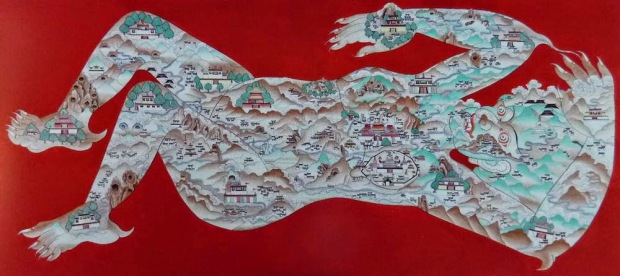

Janet Gyatso’s “Down with the Demoness: Reflections on a Feminine Ground in Tibet,” is interested in analyzing both the myth and the gendered aspect of the demoness Srin (1987). According to the myth, as recorded in the terma Mani bka’ ‘bum, the Chinese wife of King Songtsen Gampo, Kong Jo, is troubled by the amount of difficulty she is facing in “transporting the statue of Sakyamuni to the Tibetan court” (37). She has a vision where she realizes the demoness Srin, who represents the Tibetan landscape itself, is causing all the difficulties. To subdue her, they build a total of thirteen Buddhist temples, some of which still stand today in places like Bhutan (39), to pin her down on her back. Four in the inner realm of Tibet to pin her shoulder and hip. Four at the border areas, pinning her knees and elbows. Four at the boarders beyond to pin her hands and feet. And finally, one at the Jo-khang, symbolizing her heart and considered the center of Tibet (38). Thus Srin is subdued and Buddhism can reign over Tibet. Besides Buddhist domination of Srin, what is this myth really about? And why is the demoness gendered as female?

According to Gyatso, this isn’t the first time Srin is referred to as mo, female. In the Tibetan myth of the copulation between a compassionate monkey and a lustful rock ogress, which brings about the birth of the first Tibetan, Srin is portrayed as mo. In this myth, the monkey is portrayed as the male Avalokitesvara and Srin as the female rock ogress (44). Although Srin is portrayed as mo in both of the myths, whether Srin is in fact female is unclear due to a lack of sources from pre-Buddhist Tibet. For David Paul, the feminization of Srin in the Buddhist cannon may have something to do with how Buddhists of that time viewed women. Women according to Buddhists of that time were associated with desire and attachment, which was seen as dangerous and threatening to the celibate Buddhist monk (44).

Srin mo, according to Gyatso, “does not primarily represent woman, but rather a religion, or more accurately, a religious culture and world view that is being dominated” (45). In the subjugation of Srin, Srin isn’t killed, she is instead subdued and a new civilization is built on top of her, symbolized by the construction of Buddhist temples (40). Although it is the Bon tradition that is being dominated by Buddhism in the myth, Buddhism, according to Gyatso, may be “mimicking a pattern already established by Bon” (46). In Grub mtha’ shel gyi me long, “a late but well regarded account of the history of the religions of Tibet,” it is Bon that is subduing Srin, but this time, portrayed as Srin-po, male (46). Long before Buddhism, the Bon tradition, according to Erik Haarh, also invaded Tibet; Gyatso writes, “Bon-po text also contains a self-congratulatory account of the disruption and suppression of the earth beings by buildings” (50). Srin, according to R. A. Stein, belongs to an indigenous Tibetan tradition that predates Buddhism and Bon, a tradition he calls the “nameless Tibetan religion” (50). Although there are no explicit accounts of this nameless Tibetan religion, “Srin-mo is actually kept alive” ironically, according to Gyatso, through the narratives of her subjugation by the civilizations that came after and build upon her (50). So what does all this mean?

Srin, according to Gyatso, is a strong reminder to the Tibetans of their indigenous “fierce and savage” roots. Of how Tibetans view their land as a living organism that, as shown through King gLang dar ma’s concern for these beings (49), can be “violated, offended, and even wounded,” but can also be “appeased, protected, heeded, and valorized” (49). Srin also is a testament to strong female figures in Tibetan history, who Gyatso notes, were “notably more assertive than some of her Asian neighbors” (51)—accounts from the Sui shu and T’ang shu in eighth century A.D. and Tibetan texts from fifth century Tun-huang, describe matriarchal “female-dominated” societies ruled by Tibetan women, where “the supreme ruler was the queen, and sons took the family name of their mother. The men were still the warriors, but they were directed by women” (34). Her myth and her associations with femininity and indigeniety were so formidable that, as Gyatso continues, “the masculine power structure of Tibetan myth had to go to great lengths to keep the female presence under control” (50). But perhaps the most interesting aspect of Srin is the non-guaranteed aspect of her subjugation. Although she may be, “pinned, and rendered motionless” for now, “she threatens to break loose at any relaxing of vigilance or deterioration of civilization” (51). I want to draw your attention to, “deterioration of civilization.” Which I take to be a fair warning about Tibetans—especially women—from the past, present, and future.

***