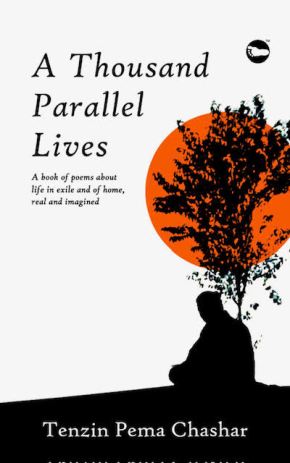

6 Poems on Life in Exile and Of Home from “A Thousand Parallel Lives” by Tenzin Pema Chashar

The first poem “The Young, the Holy, and the Wealthy” is one version of my interpretation from the many stories I’ve been told about how key members of a family, who had been identified for torture/prison/thamzing, were given fair warning from those whose loyalty the Chinese tried to buy but couldn’t.

The second poem “Here Vs. There” is something I wrote from my memory of listening to the elders talk constantly about how everything was always that much better or more abundant or brighter or bigger (even the ravens, as I recall) in Tibet. So it’s written from the vantage of someone who is about to set off for life in exile and has these hopes for how this new life/home should be.

The third poem “Wait for Me” is something I wrote from the perspective of so many of our parents and elders who had to leave their parents or children and loved ones behind as many of them had to make a hasty escape. However, many stayed somewhere close to the borders, waiting for their loved ones to join them, and not making the final descent into exile because of their belief too that the issue of Tibet would be a temporary one.

The fourth poem “Call to Arms” is about early life in exile when Tibetans in nearly every settlement called on their youth to practice ‘March Past’ every morning (with wooden toy guns) so that they would be ready if ever there was a war with the Chinese.

The fifth poem “Stone Bench” is about life in exile in the 1980’s and 1990’s when the longing for home (where the life they had left behind was home) was still palpable and a focal point of all conversations between the elders.