Ayu Khandro, the Traveling Yogini of Kham

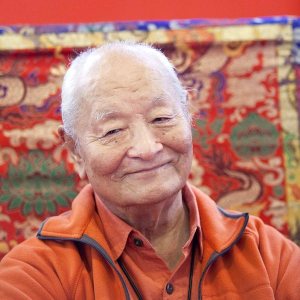

Ayu Khandro was a highly regarded neljorma, yogini, in eastern Tibet, who was born in 1839 and died in 1953 at the age of hundred-and-fifteen. Unlike Sera Khandro, Ayu Khandro did not leave behind an autobiography. Instead, Namkhai Norbu, a highly recognized Dzogchen practioner who continues to teach throughout Asia and the West, composed a short biography of her life when he was sent by his teacher in 1951, at the age of fourteen, to receive the Vajra Yogini initiation from Ayu Khandro. In the following, I explore Ayu Khandro’s spiritual journey using gender as an analytical tool. Additionally, I use Serah Jacoby’s gendered reading of Sera Khandro’s autobiography, Love And Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro (2014), to supplement my reading of Ayu Khandro’s biography. The copy I am consulting is in Tultrim Allione’s Women of Wisdom, under the title, “The Biography of Ayu Khandro, Dorje Paldron,” the book covers the namtars of several recognized Tibetan yoginis (2000). Initially, when Namkhai Norbu requested Ayu Khandro for teachings, he remembers her being hesitant, claiming she was “no one special and had no qualifications to teach” (2000: 5). However, after an auspicious dream, in which Ayu Khandro’s teacher, Jamyang Khentse Wangpo, advised her to give Namkhai Norbu the teachings of Khandro Sangwa Kundu, his gongter, she finally accepts him as her student. During the months he studied with Ayu Khandro, at his request, she told him about her life and he took down everything, from which, he constructed her namtar, biography, “for her disciples and those who are interested” (159).

In the prologue, Allione notes several special features regarding Ayu Khandro’s namtar. In addition to Namkhai Norbu’s commentaries on how her biography came into being, Ayu Khandro, according to Allione, made sure to “select…what would be relevant for another practitioner to know” (137). Allione’s suggestion implies Ayu Khandro had a target audience in mind when she told Namkai Norbu her life story. Palden and Khenpo Targyal, Ayu Khandro’s assistant and disciple, confirm this suggestion. After she had begun teaching Namkhai Norbu along with her other students, Khenpo Targyal, an abbot to a monastery, noted the extended teachings she had been giving them in such a short time, and how rare this was. He expressed feeling “afraid” that this meant she would leave her life soon. In addition, Palden told Namkhai Norbu that several months before he had arrived, Ayu Khandro had had a dream. The dream indicated “that she should give certain teachings soon,” and even before Namkhai Norbu had arrived, Palden and her other assistant, a nun, had “begun the preparations” (140) to give certain teachings. After considering everything Palden told him, Namkhai Norbu concludes, “So there was definitely a motive for [Ayu Khandro to be] giving these teachings” to him and other disciples that had gathered. If Ayu Khandro knew, as noted by Khenpo, that she was at the end of her life, and was preparing, according to Palden, to give certain teachings as instructed, then she must’ve selectively chosen, like Allione suggests, what she considered useful for Namkhai Norbu to note down, so that it “would be relevant for another practitioner to know.” While the earlier portion of her namtar provides personal insights on her life and how she came to practice the dharma, the latter parts focus more on her spiritual journey as a traveling yogini practicing chod; the different teachings she received along the way from different practitioners; and how she came to settle in Dzongsa, where she decided to stay in retreat for the rest of her life.

Ayu Khandro was born to the nomadic family of Ah-Tu Tahang in the Kham region of Tagzi, in a village called Dzong Trang. Like Sera Khandro, on the day Ayu Khandro was born, people reported auspicious signs. Togden Rangrig, a yogi who practiced near their village, who was at her home at the time of her birth, gave her the name Dechen Khandro. She was the youngest of eight children. Her mother’s name was Tsokyi but was called Atso, and her father was Tamdrin Gon, called Arta. In comparison to Sera Khandro, who hailed from a powerful aristocratic family in Lhasa, Ayu Khandro came from modest means. She describes her family as neither poor nor rich, her three older brothers became traders and her four sisters did “nomad’s work” (140). As the youngest, she mostly looked after small animals that her family owned. Like Sera Khandro, Ayu Khandro also describes being religiously inclined from a young age. However, unlike Sera Khandro, Ayu Khandro did not have to travel far to seek her spiritual mentors. Her aunt, Dronkyi, was a strong practitioner who lived near Togden Rangrig’s cave. At seven, Ayu Khandro remembers choosing at her own will, to go to her aunts’ in Drag Ka Yang Dzong. During her stay, Ayu Khandro assisted her aunt and Kunzang Longyang, Togden Ranrig’s disciple, with daily chores. Kunzang Logyang taught her and his nephew, Rinchen Namgyal, how to read and write Tibetan. Having participated in reading the Kangyur twice to extend Togden’s life, her reading skills improved.

At thirteen, she received her first initiation and teaching on the Longsal Dorje Nyingpo. Although she admits not having understood most of the teaching, she implies the practice as having elevated her faith. That same year, her parents met the Gara Tsong family, a wealthy family in Kham, who were friends and patrons of her aunt. After her aunt introduced the two families, her parents set Ayu Khandro up to be married to their son, Apho Wangdo. In a similar fashion to Sera Khandro, Ayu Khandro describes having no say in the matter and pointing out her parents desire for “wealth” as the basis for her marriage. Although her aunt tries to intervene on her behalf, asking them to let her chose her own path, they only agree to delay her wedding. At fourteen, she traveled with her aunt and Togden Rangrig to see Jamyang Khentse Wangpo, Jamgon Kongtrul, and Cho Gyur Lingpa, and traveled with them to Dzong Tsho, were she met other great practitioners. During this journey, she receives many instructions and teachings from all the teachers she comes to know. After her return, feeling more confident, she begins the preliminary practices of the Longchen Nyingtig, with instructions from Kunzang Longyang. In 1854, at sixteen, she went with her aunt to see Jamyang Khentse Wangpo (also known as Dzongsar Khentse Rinpoche) who initiates her aunt and her into the Pema Nyingthig and gives her the name Tsewang Paldron. Upon her return, she goes into her first retreat. However, her spiritual path is cut short at nineteen when her parents marry her off to Apho Wangdo. She describes her husband as gentle and kind, but she is unsatisfied. After three years of marriage, Ayu Khandro becomes sick and does not get better for two years. Togden Rangrig is called in to see her and performs rituals and divinities, but makes it clear to her husband and his family that the real cause of her sickness is that she is being forced “to lead a worldly life…against her will” (142). After listening to Togden Rangrig and Ayu Khandro’s own reasons for wanting to go back to leading a spiritual life, Apho Wangdo agrees. As soon as her health improves, Apho Wangdo accompanies her back to her aunt’s cave for her to resume her practices under the guidance of her aunt and Togden.

Despite experiencing a brief interruption on her spiritual path with marriage, the rest of Ayu Khandro’s namtar continues her spiritual path without any worldly interruptions. Following the deaths of Togden Rangrig and her aunt in 1865, Ayu Khandro enters a three-year retreat. After the retreat, at the age of thirty, she decides on becoming a traveling yogini, not returning until she’s forty-three. Over the course of thirteen years, Ayu Khandro travels all over Tibet and is joined on her travels by other yogis and yoginis. On her journey visiting sacred sites and monasteries across Tibet, she meets many highly recognized male teachers who initiate her into different teachings, and instructs her on her practice and journey. When she returns to her original place of practice, she describes having found the place in ruins. After a dream, in which, she sees herself next to an egg-shaped rock in Dzongtsa, she traveled there and experiences a miracle. Although she was across the river from the egg-shaped rock in Dzongtsa, she experiences a dream in which she walked across to Dzongtsa on a white bridge. When she awakes, she finds herself on the other side of the bank; due to the auspicious circumstances she decides to make the spot her permanent place of retreat. In 1953, at the age of hundred-and-fifteen, she passed away, despite pleas from her followers to remain longer, she refused, warning that trying times were headed their way and she would be too old to bear it.

In Janet Gyatso’s “Introduction,” of her book, Apparitions of the Self: The Secret Autobiography of a Tibetan Visionary, she discusses the purpose of spiritual autobiographies (2001). Based on Gyatso’s close reading of Jigme Lingpa’s autobiography, Gyatso concludes that the purpose of spiritual autobiographies were to; demonstrate the “authenticity” of the treasure reveler’s spiritual journey (2001: 8) and serve as an “instructive” manual for their students (10). At each phase of her journey, Ayu Khandro makes sure to give specific names of the teachers from whom she received specific teachings from—making sure to give the names of the specific teachings and the practices she incorporated at each step of the way. For instance, after recalling an incident in which her nun friend and travel companion Pema Yangkyi and her come across a distraught nomad woman who’s dead husbands body they helped carry to a cemetery, she comes across Togden Semnyi Dorje–who had been practicing at the cemetery and offers to assist them in the proper funerary practices. During the practice, he teaches Ayu Khandro and Pema Yangkyi the Zinba Rangdrol Chod (Allione, 2000: 148)—in this way, she informs her readers of her spiritual journey not just figuratively, but instructively, as suggested by Allione. While the biography itself serves to authenticate Ayu Khandro’s spiritual journey, especially when the highly recognized Namkhai Norbu composed it, there are several other factors that authenticate her biography further. For example, many highly recognized lineage holders like Jamyang Khentse Rinpoche and Nala Pema Dhondup among many others, legitimizes her path by bestowing on her teachings and instructions on her practice. While she mostly occupies the role of the student during her journey, at times, Ayu Khandro also occupied the role of the teacher—she recalls meeting Togden Trulzhi (a disciple of the famous female practitioner, Mindroling Jetsun Rinpoche), who gives Ayu Khandro and Pema Yangkyi teachings on Dzongchen Terma of Mindroling; later, he asks both women for teachings on the White Tara practice they received from Jamyang Khentse Rinpoche (150). Additionally, she records miracles, such as her dream in Dzongtsa—all of which further authenticates her status as a highly learned practitioner.

While reading Ayu Khandro’s biography, I am astounded by how different it reads from Sera Khandro’s autobiography. Ayu Khandro is much older than Sera Khandro; she outlived Sera Khandro, suggesting both women to have lived through similar timelines. Yet, in comparison to Sera Khandro, who’s life was fraught with lack of familial roots and being a woman, both of which contributed greatly to her suffering, Ayu Khandro, who shared the same gendered subjectivity of being a woman at that time with Sera Khandro, seems to have had less distractions on her spiritual path. Although they did share similar gendered difficulties, such as having to fulfill parental and societal expectations of marriage, this is where their similarities end. Although it is unfair to compare Ayu Khandro’s life to Sera Khandro, since Tibetan woman at that time did not share homogeneous subjectivities, there are several factors that should be considered in understanding why both women had such drastically different experiences on their chosen path to spiritual awakening. Did their radically different backgrounds play a role in the different outcomes of their journeys? For example, unlike Sera Khandro, Ayu Khandro did not need to go far to seek spiritual guidance. With an aunt who was already accepted and recognized by her family as a serious practitioner, Ayu Khandro was not held back from choosing to live with her aunt at a young age to nurture her spiritual interests. In Ayu Khandro’s case, it seems having another spiritual practitioner in the family who was highly regarded by other family members worked to Ayu Khandro’s advantage; both in terms of having access to a spiritual guide and getting permission from family. Sera Khandro, on the other hand, did not share such advantages and ran away in pursuit of her spiritual guide Drime Ozer to Golok.

Additionally, I wonder whether the difference between the two women’s familial backgrounds helped contribute to their different subjectivities. Scholars of Tibet have often noted how men and women of aristocratic background enjoyed less freedom than the men and women of nomadic backgrounds due to their political obligations and aspirations. Sera Khandro was born to a politically active aristocratic family in Lhasa, in comparison; Ayu Khandro was born to a nomadic family. As the daughter of a politically active figure, Sera Khandro did not lack wealth; instead, she accuses her father’s insistence on her marriage as being motivated by “power” and ends up having to run-away in order to escape his decision. While Ayu Khandro’s biography makes no references to her parents as politically motivated, she does, however, accuse her parents of marrying her off in the interest of “wealth.” Although both women’s parents seem to have worldly motivations driving their interests in marrying off their daughters, I wonder whether an in-depth analysis of the different classed subjectivities of both women and their parents, as aristocrat and nomad, could offer new insights regarding the women’s proximity to their spiritual paths. In addition to class and gender, hereditary roots also impacted both Sera Khandro and Ayu Khandro’s spiritual paths—for Sera Khandro, lacking hereditary roots in Golok meant she lacked legitimacy and was more susceptible to harm, while Ayu Khandro’s established familial roots in Kham helped, in some ways, sustain her spiritual path. An in-depth analysis of both women’s lives using class, status, and familial roots, in addition to a gendered analysis, would offer a much more robust understanding of the societies in which these women lived through and how that affected both women’s path towards empowerment and enlightenment.

Jacoby’s close reading of Sera Khandro’s autobiography reveals the struggles she endured as rooted in her gendered subjectivity as a woman who lacked class and hereditary status; yet, she achieves her spiritual goals despite these difficulties. In Ayu Khandro’s case, it is difficult to tell whether she encountered other forms of gendered difficulties, besides the troubles she had with marriage, since her biography is short and unlike Sera Khandro, is authored not by her. However, aside from her aunt Dronkyi and Pema Yangkyi, her namtar is populated frequently by male practitioners who occupied positions of hierarchies—this suggests Ayu Khandro too, like Sera Khandro, engaged a spiritual world where male practitioners dominated. Yet, both women achieved spiritual gratification through their chosen medium of Vajriyana (tantric) Buddhism despite its male dominated nature. In Hugh Urban’s “What About the Woman? Gender Politics and the Interpretation of Women in Tantra” section of his book, The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics (2009), Urban engages essentialized roles that women take on in Sakta Tantra and how they draw power from this. He writes, “Tantric women can and historically have found new room to maneuver and [create] new spaces for agency even within a highly essentialized, heteronormative, and male-dominated system” (2009: 144). While Urban is talking about women in the Hindu tradition of Sakta Tantra, his analysis could apply to Ayu Khandro and Sera Khandro. Both women traversed spiritual paths dominated by male practitioners but they achieved spiritual liberation, affirming Urban’s argument that tantric women can create spaces of agency within male dominated religious systems to empower and liberate themselves.

***

Works cited:

Gyatso, Janet. 2001. “Introduction,” in Apparitions of the self: The secret autobiographies of a Tibetan visionary (Vol. 46). Motilal Banarsidass Publ..

Urban, Hugh. 2009. The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies. IB Tauris.

Reblogged this on dlo08.

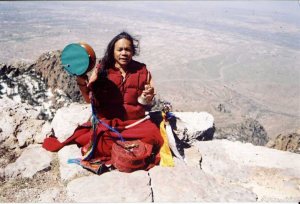

This yogi I practicing chod on a cliff top is Ngakpa karma lhundrup a man not a yogini best wishes

Cool

I am trying to attain enlightenment but I have many blockages and challenges to overcome.

I hope I can achieve this goal.