The Museum on the Roof of the World: My Take

© 2013 Dlo08

I really enjoyed reading Clare Harris’s The Museum on the Roof of the World (2012). On finishing the first half of the book, which went into detailed analysis on the political life of archival documentation, specifically images of Tibet-ans, I immediately found myself wishing I had read this book to supplement what I was missing in my last post on Lhakar Diaries, “The Art of (China’s) Colonialism: Constructing Invisibilities in (Tibetan) History and Geography”: the role of the British in constructing the Orientalized Tibetan other.

Harris brings back to life documents and images from a range of colonial archives, and includes accounts and fictions published by British officers, ethnographers, soldiers and Asia-Tibet enthusiasts of that time to piece together how the myth of the exotic Tibet-an came into existence in the West. Her analysis is based on exploring the discursive formation of how the West came to imagine Tibet and its inhabitants. She describe how representations of Tibet in these works were being informed and produced by the ideologies of that time —placing different societies in racial evolutionary scales with the West serving as the most advanced. As Harris points out, this framing placed Tibet in a desirable exotic light; as a society capable of having their own civilization and worthy of western attention. A society that was, importantly, displayed through the desire to accumulate Tibetan “artifacts.” This aspect of her argument articulates Steinmetz’s emphasis on “symbolic capital” (capital in status, not material, form) (2007). According to him, one of the ways colonial officials without hereditary status (the non aristocracy) back in imperial Germany were able to attain status was through the accumulation of symbolic capital by fashioning themselves off as experts with access to native knowledges and who demonstrated this expertise through possession of native materials that they seized from regions they invaded and occupied.

As explored by Harris, colonial British officials on the Younghusband mission in Tibet were able to sell artifacts they stole during the invasion of Tibet on their return to Britain. Some of these objects can now be viewed in different museums across the west that belong to the private collections of the families of those officials or private collectors. Those who worked as private ethnographers for the British administration were able to make careers off their oftentimes-uninformed “expertise” gleaned from their interactions with Tibetans during the invasion of Tibet.

One of the most abused picture of Tibetan nuns to this day, wearing wigs to keep their heads warm, taken by John Claude White from the Younghusband mission.

Harris does a superb job at showing how the images, descriptions, and artifacts of and about Tibet-ans did the intended work of informing the British public of how to view the Tibetans. She also does not hide the fact that these representations of Tibet also served to make Tibet a desirable space for potential British colonization. This dream was however, interrupted by India’s independence and gave way for the Chinese to intervene in Tibet.

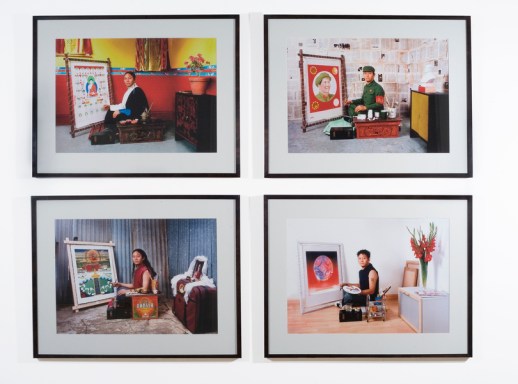

Although I cannot say enough on how historically robust and well thought out Harris’s first half of the book is, I was not as satisfied with the second half of her book on “Contemporary Tibetan Art.” She does a wonderful job explaining how contemporary Tibetan art came to be: in Lhasa. That it emerged as a way to subvert Chinese authoritarian gaze on Tibetan art-ists. Despite superb details on the art, artists, and the messages embedded within these art works, and even with the additional information about the times in which these works were produced, I was not satisfied with the lack of focus on such artworks’ audience.

Unlike the first section of her book, she does not go into who the intended and possible unintended audience for these works were. While she loosely mentions the western collectors who seem to be interested in these works for similar reasons earlier collectors were intrigued, other than mentioning the added excitement over assumed exotic natives capable of producing “modern” works of art, I saw very little discussion on the Chinese audience, and close to nothing on the Tibetan audience. I do, however, acknowledge the difficulty of such a task, it may even require a completely different project to look into those audiences.

While reading about the different artists (all based in or from Lhasa) and their work, I found myself asking; for whom are these works intended? Who is the artist producing these works for? Almost all of the artists Harris mentioned in her book produce work intended for an audience through exhibitions, showings, and installations. I am interesting in knowing whether these contemporary Tibetan artists produced specific works with an intended audiences in mind during the time of its construction. I would also be interested in who the unintended audiences were and why.

Though Harris tells us that some of the works by artists she explored hint at how some of the artists identify with not one specific identity: Tibetan or Chinese, but a possible global identity, she also points to the particularity with which these artists use iconic Tibetan symbols, especially Buddhist imagery in their works. I personally see tension between this particularity and the “global” identity, this assumed global citizenry or humanity. Through an exploration of the possible audiences, the section on Contemporary Tibetan Art could have been more powerful in describing how representations of Tibetan-ness or global-ness has manifested in the intended and unintended audiences of these works.

Works Cited:

Harris, C. E. 2012. The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet. University of Chicago Press.

Steinmetz, George. 2007. Devil’s Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

I apologize for leaving a kind of inane reply, but I just bought this book, and want to tell you that your review is already very, very helpful. It’s helping me ground it in a broader discourse as I read it. Thank you very much.

Pingback: The Museum on the Roof of the World: My Take | Tibetan Blog Station

Reblogged this on dlo08.

Pingback: How do we Tibetans create our own sense of Place? Why should it matter? |

Pingback: Tsering Yangzom Lama, Dawa Lokyitsang and Natalie Avalos at Jaipur Lit Festival |