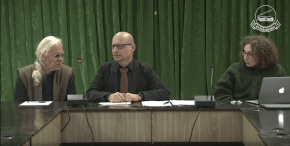

Tsering Yangzom Lama, Dawa Lokyitsang and Natalie Avalos at Jaipur Lit Festival

Long term readers of Lhakar Diaries know that Tsering Yangzom Lama is one of our founders. So it is a pleasure to share a video of us in conversation talking about her book, “We Measure the Earth with our Bodies,” and topics such as: the centrality of land in how we as Tibetans imagine and enact ourselves in the world, colonial dispossession, the coloniality of Tibetan Studies and the extractive nature with which some of its scholars engage Tibet/ans, theft of sacred Tibetan objects in the making of expertise and museums, intentionality in Tibetan Buddhist ritual practices of compassion and how its not about just the self but about all.

This conversation took place at the Jaipur Literature Festival in Boulder, CO on September 23rd, 2023.